By J.K. YAMAMOTO, Rafu Staff Writer

The family has decided that 109 years is enough, though many customers would beg to differ.

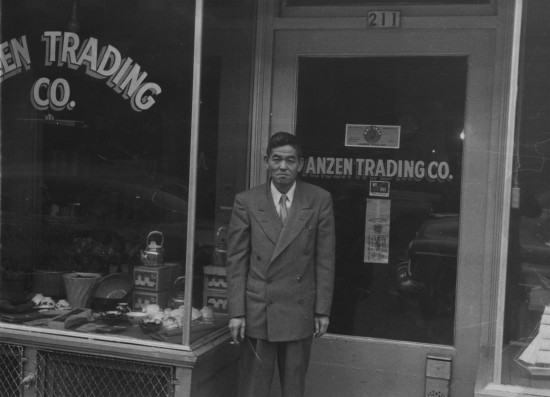

Hiroshi’s Anzen, a grocery and cookware store established in Portland, Ore. by the Matsushima family in 1905, is closing its doors on Sept. 30.

Originally called Matsushima Shoten and later known as Teikoku Company, the dry goods store was located on Third and Davis, part of a thriving Japantown that included restaurants, hotels, laundries, doctors’ and dentists’ offices, tofu and manju shops, a newspaper (Oshu Nippo), barbershops, and more.

According to the Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center, “As the number of families increased from 1910 to 1920, Japantown grew into a respectable place where children could play in the streets and visitors felt comfortable and welcome.”

Like most other Japantowns on the West Coast, the Nikkei neighborhood in Portland was never the same after World War II, though some businesses and organizations did return.

Hiroshi Matsushima, 75, the current owner of Anzen, said that when the war broke out, his grandfather, Mosaburo, had returned to Wakayama Prefecture, where he owned a house, and his father, Umata, was running the family business. Along with other community leaders, “my dad got picked up and handcuffed by the FBI” shortly after Pearl Harbor and “we had to liquidate.”

Umata was sent to a series of Department of Justice camps, including Missoula, Mont. (where Rafu Shimpo publisher Toyosaku Komai was also interned), Livingston, La., and Santa Fe, N.M.

The rest of the family was sent in May 1942 to the Portland Assembly Center, formerly the Pacific International Livestock Exposition, and later to the War Relocation Authority camp in Minidoka, Idaho.

“Then we went to Ellis Island, where we were supposed to meet up with my father and get traded for white Americans [being held by Japan],” said Matsushima, who was 3 years old when he was interned and 6 or 7 when he was released. “We were going to get on the ship Gripsholm, but my father never showed up. We didn’t know where he was for a year and a half.”

The family was finally reunited at the DOJ camp in Crystal City, Texas, and remained there until 1946, long after the war was over. They returned to Portland by way of Los Angeles, stayed with relatives, and briefly lived in Vanport, a housing project for shipyard workers that was later wiped out by a flood.

Two of Matsushima’s siblings were sent to Japan before the war for their education, a common practice among Nikkei families at the time. His sister came back in 1955, but his brother inherited his father’s land in Japan and decided to stay there.

The store, renamed Anzen, was re-established at 311 NW Davis, with the family living in the back, and in 1968 moved to its present location at 736 NE Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd. (formerly Union Avenue) in what is now Chinatown. Matsushima took over the business with his brother Yoji and has worked there for 52 years as an adult. His wife, Jane, a retired schoolteacher, is now at the store full-time.

Matsushima’s children worked at the store part-time while attending high school and college, but now “they have families of their own and they get weekends off,” he said. “My youngest son was going to [take over the business], but he decided against it … Too many hours, too many weekends, too many holidays … We’re closed six days out of the year.”

The family used to have two locations in Beaverton, Ore., but they were closed more than a decade ago after Seattle-based supermarket Uwajimaya opened a store there. Jane Matsushima told The Portland Tribune in 2003, “We were also going to shut [the MLK store] down in the first part of 2000, but we decided to try and make a go of it, mainly because Hiroshi wanted to honor his family — his grandparents, who started this, and then his mother and father, who kept it going even after the war and being interned.”

Since the announcement of the main store’s closure, Hiroshi Matsushima said, customers “all come in and say, ‘Sorry to see you leaving.’ A lot of them are friends anyway. We have some that have been shopping with us for three generations. Their grandfathers used to shop at my grandfather’s store.”

With the boom in popularity of Japanese culture, “there are lot of Caucasian customers now,” he added, recalling that one local newspaper declared Anzen’s sashimi to be “the freshest fish in town.”

Willamette Week described Anzen’s inventory as follows: “A happy jumble of Asian groceries and cookware sprouts from every available surface, even the ceiling: fresh and frozen sushi staples; hot, steamed hum bao rolls and squid salad by the pound; more types of nori than found in the Pacific Ocean; and a whole fridge case devoted to sticky fermented soybeans called natto … Plus, lovely tea and sake sets, robes and paper umbrellas.”

The “Buddha Bellies” blog praised Anzen’s “great selection of misos, traditional Japanese pickled items, soups, soba noodles and exotic Japanese items such as yam noodles and shredded taro … A great place to buy oily, melt-in-your-mouth, sushi-grade tunas.”

Gene Kusaka, who is originally from Southern California and has lived in Portland for eight years, commented, “Anzen reminded me of shops in J-Town as a kid, and growing up in Anaheim we had a small store called Nippon Foods [on Ball Road] … fresh produce, fish, Japanese groceries.

“The important thing about Anzen is that it’s a hub for the Nikkei community in the area. Whenever I was there, invariably shoppers passing by one another would know one another from the Buddhist church or some JA activity, family friends, that sort of thing. They would catch up on news.”

Although there are other gathering places such as a church and a kendo dojo, Kusaka said, “Anzen, being so centrally located and just being there for multiple generations … it did serve a very important role for the Japanese American community.”

He added, “One of the standouts about the place is … the fact that it was privately owned and not part of a large chain.”

The family created “a very friendly environment, very open, welcoming, very multicultural in its clientele and longtime patrons. Everyone that would shop there felt very welcome,” Kusaka said, and this created “loyalty to the store, an emotional bond to it as part of the community.”

Matsushima said Thursday that “the food is almost all gone,” but if there is anything left on Tuesday “we’re going to have to bring it home.”

He wasn’t sure what would happen to the space, as the family doesn’t own it. “We did at one time, but we don’t anymore.”

Asked about his future plans, Matsushima responded, “Relax, travel, read, fish … I grew up in the back of the store and started [working] when I was about 12 years old. I’ll be happy to sit back and relax.”

At the same time, he’s gratified that organizations like the Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center and the Japanese American National Museum have recognized Anzen as one of the few Nikkei-owned businesses to have passed the century mark.

HIroshi told me that he and Jane are in the phone book if I need to look them up in the future.

Great article. Any chance of getting Hiroshi’s address? His brother and he were friends that I spent time together in Minedoka and Portland. His store is truly a historical monument.